The following account was originally published in the monthly series, “Back in My Day,” in the Friday, August 25, 2006, Burleson, Crowley, Cleburne edition of the Fort Worth Star Telegram.

RECALLING CAMELOT

I had not yet started school. I was still too young. I remember we had tile on our living room floor and a big round rug covering its center in our home in south Fort Worth, Texas, that fateful November day. I was on the rug pushing my little toy cars along its circular rings, using them as miniature highways. Mom was to the side of the room near the kitchen ironing clothes. We were alone that mid-day. Dad was at work. My older brother and sister were at school.

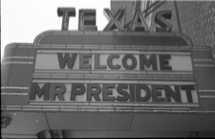

The television was on. I believe one of Mom’s soap operas had been playing. Suddenly there was an interruption in the program. The usually calm, soft, black and white images were replaced by grainy, violent ones that jerkily danced across the screen. Firm, yet shrill, excited, new voices spoke over it. I don’t recall paying it a great deal of attention at first until I realized that mother had stopped ironing and was gazing intently at the television. I was aware that the room had grown still. After a few moments, I looked up at mother and was surprised to see that her eyes were full of tears. A single one had tumbled over her eyelid and was rolling down her cheek. Her hand was drawn up to her open mouth. Later I would learn that the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, had been assassinated just moments earlier nearby in Dallas.

For the next several days, our family, like countless others across America, sat transfixed to the television watching the continuing coverage of the shocking events of the weekend. Then, the funeral came.

For such a young boy as I was, it surprises me even now all that I remember. I wonder yet why it so captivated me then, why it captivates me still. Of all that happened on the day the President was buried, I will never forget the rider-less horse, with the empty boots turned backwards in its stirrups, and its single attendant that marched in the center of the streets of Washington. While everyone else marched calmly, orderly down the lanes, that horse alone refused to stay in step. Relentlessly he fidgeted and snorted about as though frightened by the expectation of a ghostly hand’s touch.

Without being able to adequately explain why, the assassination became a watershed event, a subliminal moment for my generation and those just a little older. Too young at the time to understand all it meant, I have inexplicably developed over the intervening years an obsessive, personal interest in it and the young, vibrant President whose life was so horribly ended.

Now more than forty years later, at least a couple of dozen books and several videos on the assassination or President Kennedy’s life sit on my bookshelf like gothic specters with a haunting gaze. I often find myself feeling just a little ill at ease, rummaging through them with a quiet desperation as though searching for answers to unspoken, unknown questions.

Like a flood of others, I have been drawn to Dealey Plaza in Dallas where it occurred. I’ve viewed it from many angles. I’ve touched the splintering wood of its grassy knoll’s picket fence, heard the clatter of slow moving railroad cars in the nearby switching yard and, standing on the sidewalk near the point where the young prince fell, strained to listen for the faded echoes of the rifle shots.

I’ve toured the Sixth Floor Museum of the Texas School Book Depository that now occupies the sniper’s roost overlooking the plaza. I’ve peered down through the dusty glass of the sixth floor windows into the streets and intersection below and tried to imagine what that day looked like through the killer’s eyes.

Why does that day hold such fascination? There’s no easy or certain answer. Perhaps the bullets shattered more than Governor Connally’s body or the President’s life that day. Perhaps they ripped away and disquieted a whole generation’s child-like sense of innocence and security. One day, our lives were fraught with astonishing wonders and delights. In a flashing, searing moment, all that was changed. Like hearing a loud trumpet blast too near the ears, which deadens our hearing, rattles our eyesight so that we see a kaleidoscope of quaking, distorted, indistinct images and which frightens us into bolting upright, we flung off, all too soon, a veil that day to awaken to the harsh and terrifying realities of the world. And, like that rider-less horse, we are restless, anxious and afraid of ghostly hands that may yet caress us if we, too, stand still.